CHAPTER ONE

Waypoints is a learning system rooted in primary sources that explores and fosters an understanding of liberty. In the following chapters, we will discuss what primary sources are and why supplementing traditional curricula with them is important. This opening chapter clarifies what we mean by a learning system for liberty.

The Challenge of Liberty

Throughout human history, regimes of liberty have been outliers because liberty demands much from its citizens and institutions. To live freely and govern oneself alongside others requires a government powerful enough to protect the individual rights of citizens from foreign and domestic threats, but limited enough to avoid abusing power or violating the rights of citizens.

Such a government requires vigilant citizens who ensure that those in power exercise only the limited authority delegated to them. A government of limited and delegated powers also requires citizens who are self-restrained, self-governing, fiercely self-assertive, and productive and self-reliant.

Free, self-governing citizens must also possess a strong foundation of civic knowledge, including an understanding of their own personal responsibilities as well as the proper and narrow purpose of government (protecting the natural and civil rights of individual citizens), and the limited powers necessary to achieve that limited purpose.

The Role of Ideas in Sustaining Liberty

The cultural, moral, and political conditions that sustain liberty and human flourishing arise from key ideas of liberty. By encouraging students to study these principles, apply them to public policies (or the decision not to create policies) when they are old enough to vote, and use them as guides for personal and political decisions, Waypoints prepares them to become good citizens and free, happy people.

This is the ultimate purpose of the Waypoints learning system.

Key Ideas and Primary Sources

The Waypoints system presents a curated selection of primary sources that illuminate the key ideas of liberty. These include:

These works provide essential counterpoints, helping students grapple with competing ideas and deepen their understanding.

Explanatory Essays and Tutorials

Waypoints provides explanatory essays and tutorials that clarify how each curated primary source document—whether aligning with or opposing the principles of liberty—contributes to a richer, deeper understanding of these ideas and their application to real-world situations.

By engaging with these materials, students not only learn the timeless principles of liberty but also develop the critical thinking skills needed to navigate complex issues as informed and responsible citizens, and as moral, self-governing human beings.

Here are 24 key ideas of liberty and related concepts found within in the Waypoints collection of primary sources and featured in the Waypoints explanatory essays and tutorials:

1. Business

It is not uncommon to hear people assert that businesses are especially corrupt, greedy, and even looking to hurt people if they are not closely monitored and regulated. But one cannot know whether the allegations against businesses are true without first knowing what a business is. What, then, exactly, IS a business?

A business is organized, specialized labor and other resources for the purpose of increasing productivity.

Organizing specialized labor—people with particular talents, skills, or knowledge—and other resources—including capital and raw materials—that are specialized for specific work makes a business efficient, and efficiency is productivity.

Consider, as just an example, the smart phone that is likely in your pocket right now. It was made by a business. You could try to make a smart phone by yourself, from scratch. You could hire a team of scientists, engineers, and researchers to develop the technology needed for the phone. You could go around the world and try to get all the raw materials needed for the phone’s hardware, and you could then hire people to design and build the machinery necessary to turn the raw materials into refined, useful materials. And maybe at some point, after some assembly and programming, you might have a useable smart phone (and you might not if the phone doesn’t actually work).

That would not be a very efficient way to get a smart phone. It would cost millions or even billions of dollars, many years of time, and the expenses of many trials and errors.

An alternative would be to walk into a business that sells smart phones (or order one online), pay several hundred dollars, and immediately become the owner of a working, useable smart phone that’s probably much better quality than anything you could make on your own.

Let us address the simple question: Why is the smartphone you purchased in a store so good, so (relatively) cheap, and instantly available? The answer is: The company that makes and sells smartphones is a business. Every business is an organization that features specialized labor and resources, which makes businesses efficient and productive.

Typically, a business that makes something or offers some service—daily—can make the thing or perform the service far more efficiently than you can.

Just imagine if you tried to make all the things and do all the services for which you typically pay businesses: Imagine trying to build, repair, and paint your own house—cultivate, harvest, and prepare your own food—build your own car from scratch—weave your own cloth and make your own clothes—make your own computer—invent your own medicines—etc. Such an exercise of the imagination makes it clear that businesses are efficient and productive precisely because they organize specialized labor and other resources.

Where there are more businesses, there is more productivity because there is more efficiency. Where there are few or no businesses, there is little productivity because each individual person, trying to do everything for and by himself, is not very efficient.

2. Capital

Capital determines whether a society will be prosperous or poor, well-fed or not, populated by independent and self-reliant citizens or dependent subjects. An abundance of nutritious food, clean water, sturdy homes, safe modes of transportation, reliable sources of heat and power, modern medicines, and many other products and technologies that improve the quality of human life are impossible without capital.

A teacher can help students understand what capital is by encouraging them to think of capital as an individual’s “starter pack” for being productive and getting things done. Capital includes the tools, money, and other valuable resources a person needs to create something of value, or to solve a problem in order to create wealth.

For example, if you wanted to start a lemonade stand, the money you use to buy cups, lemons, and sugar is capital. While money is one and an important form of capital, capital can include other resources that help you create wealth for yourself by producing value for others.

Other Kinds of Capital:

Why It Matters:

Capital is anything you can use to “build” something that will provide experiences of value for other people. Money is the most obvious example of capital, but creativity, friendships, and even your honesty and intelligence, can be just as important, maybe even more important in some circumstances.

So, yes! Capital isn’t just cash. Capital includes any resource that helps you be more productive. Ask students: What kinds of capital do they have? Maybe it is their energy, ideas, or even their ability to make people laugh. Remind them that everyone—even people with little or no money—have important capital over which each person has much control: His own reputation, honesty, and trustworthiness.

Evaluating incentives

One of the most important questions within any society is: Who will allocate capital? One possibility is that individuals choose whether, how, when, where, and why to spend their own money and invest their own capital. Another option is that political elites within government tax and confiscate the wealth that other people create, and then choose how to allocate other people’s capital.

Individuals choosing how to invest their own capital have strikingly different incentives than politicians and bureaucrats in government spending other people’s money.

As we discuss in another section, profit is the happiness of other people. When individuals and business owners make their own choices about how to allocate and when to invest their own capital, they aim to earn a profit—they want a return on their investment—which is another way of saying they’re trying to make other people happy by producing value for them.

When those in government choose how to spend other people’s money, they serve their own interests, usually by expanding the scope and power of government and controlling other people. That is worth repeating: Business owners allocate their own capital in order to make a profit for themselves by making other people happy; government allocates other people’s capital in order to control people.

Every new government spending program, after all, requires expanding the class of unelected bureaucrats, adding new levels of control over what citizens may do, and adding new kinds of taxpayer-funded government competition to businesses and other private organizations.

Incentives of Allocation

For politicians and bureaucrats, resource allocation often means achieving political ends or aiming for short-term gains. Without direct knowledge of costs or profits, these decisions can be quite unpredictable.

When private individuals choose how to invest or spend their own money, they have strong incentives to make careful, strategic decisions. If they invest wisely, they personally reap the rewards; if they invest foolishly, they suffer the losses. This direct link between decisions and consequences encourages efficiency and accountability. Individuals are motivated to seek the highest return (or best use) for their funds, and they also bear the risk of losing their capital if a project fails.

By contrast, when those in government take capital from citizens through taxation, politicians and bureaucrats end up allocating resources that are not their own. As a result, several distortions can arise:

Politicians and bureaucrats do not directly reap the profits if a particular investment yields a high return, nor do they personally bear the losses if it fails. Their reputations and job security may be at stake to some degree, but they do not face the same financial risks as private investors. This weaker “skin in the game” can lessen the incentive to make prudent decisions.

As government officials allocate money that does not belong to them, they often base funding decisions on political considerations—such as pleasing key constituencies or fulfilling campaign promises—rather than on efficiency or profit potential. They may also lack reliable market signals (like prices, profit, or loss) that help private individuals gauge the success of a venture.

In free markets, private investors rely on price mechanisms, profit/loss calculations, and personal expertise to guide decisions. Government agencies, on the other hand, often do not have the same depth of on-the-ground information or the constant feedback loop of profits and losses. This makes efficient capital allocation highly unlikely when those in government spend other people’s money.

A classic observation—attributed to Milton Friedman, and explained in the section Incentives Matter—is that people tend to be less cautious and more prone to overspending when choosing to spend other people’s money on other people’s projects. In a government context, taxpayers’ funds can end up allocated in ways that ignore cost, quality, and results.

In short, when individuals allocate their own funds, they have personal incentives—financial risk and reward—to be careful stewards of their capital. When governments collect taxes and decide how to spend them, officials are allocating other people’s funds and often do so under weaker incentives for efficiency, with less direct accountability for mistakes, and with political or bureaucratic considerations that can overshadow the goal of maximizing societal well-being.

3. Citizenship

Good government and a free, prosperous society are impossible in practice without citizens who take care of themselves and keep their government in check. In short, good government requires good citizenship.

There are four basic civic virtues that, together, form the core of being a good citizen:

Self-Restraint: Governing one’s self, especially one’s own temper and temptations to violate the rights of others.

Self-Assertion: Every citizen should be willing to defend his own individual rights and protect those he loves as well as his own property. Think of the spiritedness represented by the Gadsden Flag and its famous motto: Don’t Tread On Me!

Self-Reliance: By being productive and creating wealth by producing value for others, a citizen can take care of himself, his family, and be independent rather than dependent.

Civic Knowledge: Each citizen should understand his individual rights & personal responsibilities, as well as the limited, proper purpose of government.

4. Civil Rights

The term “civil rights” refers to the legal rights that protect the natural rights of citizens and enable them to participate in the governance of civil society.

Unlike natural rights, which exist by nature—and which are discussed in the Natural Rights section (#11) below—civil rights must be created by legislation; they are dependent on law. Civil rights typically include:

These rights must be created by law. Elections, for example, do not occur naturally; they must be planned, announced, and regulated by laws, which also define voter eligibility, the kind of ballots that will be counted, deadlines for submitting ballots, etc.

Similarly, trials and jury systems, government offices, and titles and deeds require legal frameworks to exist.

Ultimately, the purpose of individual civil rights is to acknowledge and protect the natural rights of individual citizens. For example, the legal civil right to vote supports your natural right to legitimize governance through the consent of the governed.

Because we understand natural rights as natural rightful claims to life, liberty, and property, Americans can recognize when the civil rights movement has succeeded: An American civil rights movement has accomplished its goal when civil laws provide equal protection for the liberty and property of each and every United States citizen.

When every citizen has legally ensured rights to vote, to seek justice in courts, to be tried by peers, to hold office and exercise constitutional powers, to speak and worship freely, to choose with whom they want to associate (and not associate), the civil rights movement has achieved its aim.

The concept of civil rights, however, has become a source of great political controversy in the United States because there is little agreement about what civil rights are, or what civil rights should be.

To understand how the idea of civil rights was changed—and turned into a political controversy—we must briefly revisit the 1960s.

The 1960s

Many Americans view the 1960s as a decade of radical activism that spurred significant political and cultural change, which is true. It is also true that the 1960s transformed the United States, as a regime, far more than most realize. Nothing symbolizes this radical, almost revolutionary, change more than the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which represented a political and constitutional paradigm shift—a turning point beyond which there was no going back.

With Democrats controlling both the U.S. House of Representatives and the Senate, about 60% of Democrats in both chambers voted for the Civil Rights Act. Additionally, 80% of House Republicans and 82% of Senate Republicans supported it. President Lyndon Johnson, a Democrat, signed the act into law on July 2, 1964, just two hours after being passed in Congress.

Written in response to civil rights protests, acts of violence by the Ku Klux Klan, and televised police brutality against black Americans in places like Mississippi and Alabama, the primary goal of the Civil Rights Act was to address these social ills and injustices.

The sweep of the act was unprecedented: It banned racial discrimination at voting booths (Title I); in hotels, restaurants, and theaters (Title II); in public facilities like libraries and restrooms (Title III); and in public schools (Title IV). It also expanded the jurisdiction and authority of the federal Civil Rights Commission (Title V), which now has oversight over all businesses and organizations receiving federal funding (Title VI).

Additionally, it prohibited racial discrimination within privately-owned businesses regarding hiring, firing, pay, and promotions (Title VII).

Barry Goldwater, then a U.S. Senator and a champion of racial desegregation in his home state of Arizona, voted against the Civil Rights Act primarily due to his opposition to Title II (covering businesses labeled as “public accommodations”) and Title VII (employment discrimination within private businesses).

As Senator Goldwater explained, the Constitution grants the federal government no authority to command or control who United States citizens invite into their privately-owned businesses—which is private property—with whom they must trade, or to whom they must offer jobs.

(For an example of black Americans who created enormous amounts of new wealth and prospered—long before the Civil Rights Act of 1964—please see this essay on Black Wall Street.)

Goldwater was correct. And, few people cared. Most Americans viewed the Civil Rights Act as moral redress and atonement for past racial injustices. Unlike Goldwater, many Americans did not care if the act was Constitutionally illegitimate. For them, it was morally legitimate and that’s all that mattered.

The effects of the 1964 Civil Rights Act have extended far beyond the law’s text, fueling a whole new political vocabulary—the language of civil rights—and providing a new kind of moral authority for government in America.

Before 1964, government legitimacy derived from the consent of the governed, and its powers were limited by the U.S. Constitution. After 1964, we have a government whose moral authority is inseparable from its responsibility to protect, provide, and subsidize “civil rights,” the definition of which is always changing, and expanding.

The New Regime of Civil Rights

From a progressive perspective—and we now inhabit a postmodern progressive world, so the progressive view matters much—new definitions and expansions of civil rights are viewed as essential indicators of social “progress.”

How do we know that we are making “progress” as a society? The answer: We have more rights than we used to have.

There are two pillars of this new progressive regime of civil rights.

The first is the redefinition of civil rights and the introduction of new ones. Civil rights, as previously explained, used to encompass voting, jury trials, and similar rights. Then, in the 1960s, the term included the civil right to swim in a public pool or attend a public school, as well as the civil right to dine in a restaurant where one is not welcome, to be offered a job a business owner doesn’t want to offer.

Following the 1964 Civil Rights Act, almost every progressive political agenda has been framed in terms of civil rights:

Whatever the next progressive agenda item may be—for which there is no Constitutional power granted to government—label it as a matter of “civil rights,” and the moral momentum behind it becomes virtually unstoppable.

The progressive regime of civil rights is incompatible with the United States Constitution for a simple reason: The Constitution enumerates and limits the powers of government. An infinitely evolving and expanding set of civil rights that are meant to satisfy infinitely evolving and expanding human desires requires unlimited government power.

For instance, if there is a civil right to a higher minimum wage, this necessitates laws, regulations, and bureaucrats to force business owners to pay employees more than some businesses can afford (which is why increases in the minimum wage are usually followed by some businesses laying off employees, and other businesses simply closing).

Similarly, claiming a civil right to live in an environment free from human-caused climate change demands expansive government powers to control what human beings do and the carbon footprint they leave behind.

See how it works? Executive orders, lengthy litigation, and court-enforced redresses and consent decrees turn progressive demands into policies within our post-constitutional regime of civil rights.

Discrimination

The second pillar of the new progressive regime of civil rights is a redefinition of the word “discrimination.”

The English word “discriminate” has its roots in the Latin verb discriminare, meaning “to separate” or “to distinguish,” and is closely related to another Latin term, discriminis, meaning “a dividing line” or “distinction.”

Historically, to discriminate meant to choose well or to be good at making important distinctions. Being discriminating was considered a virtue, an excellence—the ability to differentiate between high art and vulgarity, fine wine and vinegar, philosophy and sophistry, statesmanship and demagoguery, unpopular truths and popular lies.

Today, however, progressives have imbued the term with a negative connotation, associating discrimination with deep immorality and injustice. In the new progressive civil rights regime, to “discriminate” is now among the greatest of great of all moral and legal offenses. If you discriminate, you are a bad person, a bad citizen, and likely a criminal.

Since the Civil Rights Act of 1964, we’ve created extensive laws and regulations—millions of pages worth—greatly expanding the grounds for finding someone or some organization guilty of discrimination, all in the name of “civil rights.”

We have empowered and incentivized bureaucrats, lawyers, prosecutors, judges, activists, intellectuals, and pundits to serve as vigilant overseers, always on the look-out for anyone who dares to make his own choices, to be non-compliant, to discriminate.

The truth is that everyone discriminates, daily. All people discriminate about where they don’t want to go for lunch, what flavor ice cream they don’t want eat, who is not welcome at their backyard BBQ, the schools to which they won’t send their own kids, which news source they don’t trust, and who they won’t accept as a business partner.

Yet, at the same time, many Americans feel strongly, deep down, that discrimination is somehow “just wrong.” That’s how powerful the moral conditioned response is to the word “discriminate” in our progressive regime of civil rights.

As long as the progressive agenda of regulatory control and central planning continues to be framed as “civil rights,” those who value freedom are at a significant disadvantage. After all, who wants to advocate in public for fewer civil rights, rather than more?

To a large extent, this new language of progressive civil rights and the moral authority it has granted to the federal government precludes any serious discussions about the Constitution.

Progressive civil rights advocates say, in effect: “There are new civil rights to implement! These rights are expensive. They require lots of other people’s money and armies of bureaucrats to regulate and control citizens. We don’t have time to talk about the silly Constitution! To boot, the only people who bring up the Constitution are those who DISCRIMINATE!”

Concerns about the Constitution are frequently waived off dismissively in the face of urgent progressive policy initiatives promoting expanded “civil rights.”

Where We Are

This is where we find ourselves today. We now live in a post-constitutional regime of progressive civil rights.

Changing the paradigm in which we now live will be no small or easy matter. But it cannot be done at all—we cannot replace our current regime of progressive civil rights with a regime of liberty and traditional constitutional civil rights—if we do not first understand where we are and how we got here. And the 1960s, especially the 1964 Civil Rights Act, are big pieces of that story.

5. Competition

Competition produces excellence in sports, business, and many other human endeavors by fostering innovation, accountability, and the relentless pursuit of improvement.

In competitive environments, individuals and organizations are driven to outperform rivals, leading to breakthroughs in skill, strategy, and efficiency. Conversely, the absence of competition often breeds complacency, stagnation, and a decline in quality, as the urgency to adapt or excel diminishes.

The Power of Competition

In sports, competition pushes athletes and teams to refine their abilities. For example, the rivalry between Roger Federer, Rafael Nadal, and Novak Djokovic in tennis has elevated the sport’s technical and physical standards, with each player innovating new shots, strategies, and training regimens to outpace the others.

Similarly, in business, markets thrive when companies compete for customers. Apple and Samsung’s smartphone rivalry has accelerated advancements in camera technology, battery life, and user interfaces. Competition also incentivizes accountability: Underperforming sports teams face relegation, while businesses risk losing market share if they fail to meet consumer demands. This dynamic ensures a constant drive for improvement, as stagnation equates to failure.

Competition also sparks creativity. In science and technology, the 20th-century Space Race between the U.S. and USSR led to unprecedented innovations like satellite communications and microelectronics. When individuals and groups compete, resources are funneled into research, talent development, and risk-taking, yielding outcomes that might otherwise take decades to achieve.

The Cost of No Competition

In contrast, monopolies or non-competitive environments often lead to decline. For instance, state-run industries in centrally-controlled command economies (such as the Soviet Union and communist China) historically suffer from inefficiency and low-quality output due to lack of market pressure.

In sports, athletes training in isolation without rivals may plateau, lacking the external benchmarks that reveal weaknesses. Similarly, academic institutions without competitive admissions or grading systems often produce graduates ill-prepared for real-world challenges, as mediocrity goes unchallenged.

Even in arts and culture, competition—such as film festivals or literary awards—pushes creators to hone their craft in order to best their competitors. Without such benchmarks, artistic innovation can stagnate, as seen in state-controlled media systems that prioritize propaganda over creativity.

Ultimately, competition’s greatest power lies in its ability to transform potential into achievement. It creates a feedback loop where success is measured against others—in terms of wins and defeats, profits and losses, increased market share versus decreased market share—compelling individuals and organizations to improve or perish.

Without competition, the absence of stakes or benchmarks dulls ambition, leaving excellence unrealized. So long as individuals enjoy equal protection of the laws for their equal individual rights, competition propels real, measurable social, economic, and cultural progress.

6. Consent

After reminding readers of “certain unalienable rights” that all human beings possess—including “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness”—the Declaration of Independence explains “that to secure these rights, governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.”

This passage highlights foundational moral-political principles that the purpose of government is to “secure” the individual, equal natural rights of citizens—that is, the individuals who consent to establish a government and maintain that government once it becomes operational.

Rather than asserting that kings and other government officials hold power by divine right, hereditary privilege, or mere superior force and violence, the Declaration asserts that for a government to be morally legitimate, it must be authorized by the consent of those who are governed. Any government that exercises power over people without their consent is a morally illegitimate government.

Active, voluntary consent is important in two ways: In creating a government and maintaining a government.

The first meaning of consent—people agreeing to create or form a new government—is evident in the first sentence of the United States Constitution: “We the people of the United States… do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.”

The second meaning of consent—citizens giving their permission (or withholding their permission) for what those in government have been doing and plan to do in the future—is evident in frequent elections held at regular, lawful, publicly-known intervals.

Influenced by Enlightenment thinkers—particularly John Locke—this concept emphasizes that citizens enter into a social contract, or an agreement, with each other to form a government for the purpose of protecting the inherent, unalienable rights of each citizen.

This arrangement means that a government’s “just powers” are limited to those powers necessary for safeguarding these rights. If a government exercises powers to which the people have not freely consented, or if a government fails to protect the basic liberties and property rights of citizens, it is no longer a legitimate government

When the Declaration was written and adopted by the Second Continental Congress, this political philosophy—this idea that consent is necessary for political legitimacy—directly challenged monarchical rule and the widespread European belief that it was legitimate for a king to rule without the consent of his subjects because God (allegedly) bestowed legitimacy on the king.

The American revolutionaries-turned-founders disagreed. They argued that a legitimate government must rest on the popular sovereignty of the people: the notion that ultimate political power remains with the citizens themselves. When the people withdraw their consent—when, for instance, a government becomes tyrannical or ineffective at protecting the individual rights of citizens—the people always retain the natural right to alter or abolish that government and consent to establish a new one that is better designed to protect their natural liberty and private property.

Thus, “deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed” underscores the Declaration’s central theme: A legitimate government must protect the individual rights of citizens and remain accountable to the citizens from whom it claims its authority. If any government fails in these duties, the people possess the moral and political authority to revoke their consent and seek a form of governance aligned with their inherent, unalienable rights.

7. Constitution

The word constitution has two meanings, both of which are important for understanding the conditions of freedom and human flourishing.

When used as a common noun—with a lower-case “c”—constitution has a meaning that stretches back to classical Greek and Roman political philosophy. The constitution of a political community is broader than a written legal document. It embodies the fundamental principles, moral values, social structures, and institutional frameworks that collectively define a way of life.

The classical meaning of constitution can include a fundamental written law—such as the United States Constitution, or the basic legal framework of government for any nation—and more:

Another way to think about the classical meaning of constitution is to ask about any particular regime: What constitutes this regime? How is this regime different from another regime? For example: In what ways does Athens differ from Sparta? In what ways does the United States differ from the United Kingdom, France, Russia, Mexico, or China?

To address these kinds of questions is to think about constitution in the classical meaning of the term.

Modern constitutionalism has become more legalistic and formalized, pointing to a particular written legal document. In the case of the United States, there is a formal Constitution that was written in 1787, adopted in 1788, and has been amended 27 times.

The United States Constitution stands as a paragon of constitutional design. Several key features—that collectively establish a robust framework for governance, protect individual liberties, and ensure adaptability over time—make the U.S. Constitution an example that people around the world study. In particular, the Constitution stands as model of combining the consent of the people with the proper purpose of government—protecting the natural liberty and private property of each and every citizen.

Separation of Powers and Checks and Balances

One of the Constitution’s wisest and most important features is the separation of powers among the legislative, executive, and judicial branches. This constitutional division of power—when adhered to—ensures that no single branch of government becomes too powerful, fostering a system of checks and balances. For instance, while Congress makes laws, the President can veto them, and the Supreme Court can declare them unconstitutional. This interplay among the branches is a great check against tyranny and also promotes constitutional deliberation—as each branch questions whether the other branches are exercising proper constitutional powers or not—enhancing the quality of governance.

Federalism

In addition to separating powers among the legislative, executive, and judicial branches of the federal government, the Constitution also separates power between the federal and state governments through federalism. This structure allows for state-based local self-government, enabling states to address their unique needs while maintaining national unity. By differentiating the few powers delegated to the federal government, and the vast powers reserved to the states, the Constitution incentivizes diversity of state governance and fosters innovation at the state level without compromising the integrity of the union.

Flexibility and Amendments

The Constitution’s ability to adapt through a structured amendment process is another testament to its wisdom. While it establishes a stable foundation, the amendment process allows for necessary changes in response to evolving societal values and challenges. This balance between rigidity and flexibility ensures that the Constitution remains relevant without sacrificing its core principles, a flexibility that many other constitutions lack, often becoming outdated or too easily altered.

Representative Constitutional Republic and Rule of Law

The Constitution establishes a representative constitutional republic, where elected officials are accountable to the people. This system promotes responsiveness and accountability, ensuring that those in government must answer to the citizens who elected them. Coupled with the rule of law, which mandates that laws apply equally to all citizens and government officials, the Constitution aims at a society of justice and equal protection of the laws. The independence of the judiciary further reinforces these principles by empowering courts to interpret laws without immediate political interference, ensuring impartial justice.

Judicial Review

The power of judicial review, established by the landmark 1803 case Marbury v. Madison, empowers the Supreme Court to announce and explain when particular statutory laws violate the Constitution. This mechanism upholds constitutional supremacy and maintains the integrity of the legal system. By enabling the judiciary to act as a guardian of the Constitution, judicial review—when the Supreme Court exercises that power properly and in the service of the Constitution—prevents abuses of power from legislative majorities in Congress and Presidents, ensuring that all branches adhere to constitutional mandates and limitations on power.

Clarity and Brevity

The United States Constitution’s clarity and brevity contribute significantly to its effectiveness. Comprising only seven articles and 27 amendments, it outlines fundamental structures and principles without unnecessary complexity. This conciseness makes it accessible and understandable, facilitating widespread adherence and respect. In contrast, many other constitutions are lengthy and convoluted, making them difficult to navigate and enforce consistently.

8. Equality

Natural human equality is a foundational principle for a free and just society.

It is true that “all men are created equal,” as stated in the Declaration of Independence, because the word “men” is synonymous with “humankind” and every human being is, in fact, equally human.

Monarchy and slavery are wrong for the same reason: They’re both violations of natural human equality.

9. Federalism

In the section on competition, above, we explained how competition produces excellence. The United States Constitution features federalism, which is important for several reasons, one of the most important being that it incentivizes competition between and among states—and competition produces excellence.

Federalism is the division of power between the national (or federal) government and state governments. Federalism is a cornerstone of the U.S. Constitution designed to prevent tyranny, promote innovation, and ensure accountability.

By dispersing power, federalism creates a dynamic system where states and the federal government check each other’s power while fostering competition among states. This competition—driven by the mobility of citizens, businesses, and resources—serves as a critical safeguard against abuses of power and incentivizes good governance at the state level.

Preventing Centralized Tyranny and Encouraging Local Governance

Federalism’s primary benefit is its structural defense against concentrated power. By reserving certain powers to states (e.g., education, criminal justice, and infrastructure), the Constitution ensures no single entity monopolizes control.

This decentralization forces states to act as laboratories of self-government, a concept Justice Louis Brandeis famously described, where they experiment with policies tailored to local needs. If one state adopts a good policy or law, other states can do something similar. Conversely, if one state adopts a policy that turns out to be disastrous, the damage is limited to one state rather than the entire nation.

Competition as a Check on Power

Federalism’s genius lies in its creation of a competitive “marketplace of governance.” States must attract residents, businesses, and investment by maintaining fair laws, efficient public services, strict protection for property rights, and responsive policies.

If a state imposes oppressive regulations or excessive taxes, individuals and companies—especially those with capital—can relocate to states offering better conditions. This mobility pressures states to avoid abuses—such as overreach in taxation or infringement on civil liberties—and instead prioritize transparency and justice under the laws.

Incentivizing Good Governance

Competition compels states to improve services and policies to remain attractive. States with robust education systems (e.g., Massachusetts) or business-friendly regulations (e.g., Texas) often outperform others economically, creating a ripple effect as neighboring states adopt similar strategies. This rivalry also encourages fiscal responsibility: States balancing budgets without excessive debt (e.g., Utah) set benchmarks for others. Conversely, states failing to address corruption or inefficiency—such as Illinois’ pension crises—face population decline and economic stagnation, reinforcing the need for accountability.

Contrast with Non-Competitive Systems

In centralized national systems without state autonomy, governments face fewer incentives to innovate or address local needs. For example, unitary nations like France historically struggled with regional disparities, as top-down policies often ignored local contexts. By contrast, U.S. federalism allows states to address unique challenges, while the threat of citizen mobility ensures accountability.

Conclusion

Federalism’s competitive framework transforms governance into a self-correcting system. States, aware that their residents and resources can leave and move elsewhere—and take their votes and capital with them—are pushed to govern justly and efficiently. This dynamic not only checks abuses but also cultivates a culture of responsiveness and creativity, proving that competition among states is as vital to republican self-government as the separation of powers itself.

10. Incentives Matter

Economists and other social scientists often emphasize that incentives matter to explain how individuals and organizations respond to the rewards or possible penalties associated with their actions.

Within businesses, for example, incentives are closely tied to profit and efficiency. Owners and managers have strong motivations to minimize costs, maximize customer satisfaction, and innovate because their success depends on the ability to compete in the marketplace. Failure to deliver value leads to losses, bankruptcy, or being outperformed by competitors.

Government programs, however, operate in a different incentive structure. Since they are funded by taxpayer money and not subject to market competition, their survival and expansion are often influenced by political priorities rather than performance or efficiency. This can lead to perverse incentives—where programs grow regardless of whether they deliver effective outcomes. Bureaucrats and administrators may focus on expanding budgets or meeting regulations rather than ensuring efficiency or accountability.

Understanding that incentives shape behavior helps explain why government programs are often inefficient, wasteful, and even counterproductive, while private businesses are driven to adapt and innovate under the pressures of competition.

The economist Milton Friedman developed an insightful and useful framework for understanding how people spend money, which are examples of the principle that incentives matter. Sometimes referred to as the Four Ways of Spending Money, within Waypoints we will call it Friedman’s Spending Matrix.

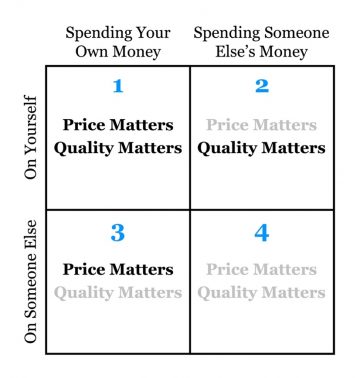

Friedman’s Spending Matrix categorizes spending into four types based on two key dimensions:

Quadrant 1: Spending Your Own Money on Yourself

Quadrant 2. Spending Other People’s Money on Yourself

Quadrant 3. Spending Your Own Money on Someone Else

Quadrant 4. Spending Other People’s Money on Someone Else

Efficiency: The least efficient type of spending due to lack of direct accountability.

Efficiency: The least efficient type of spending due to lack of direct accountability.Applications and Importance

Friedman’s matrix highlights the natural trade-offs and distortions in decision-making when incentives change. It underscores the inefficiencies of government intervention and the importance of personal responsibility and market-driven spending.

It is helpful to remember that Quadrant 4 choices are typically the worst quality of choices—and that all government spending programs are Quadrant 4 choices. From these principles, a rule of thumb follows: When something doesn’t seem to make sense, or a program receives more funding even though it doesn’t achieve the results that have been promised, government is usually involved either directly or indirectly.

11. Justice

“Justice is the end of government,” The Federalist Papers #51 famously announced. Justice “is the end of civil society,” and it “will be pursued until it be obtained, or until liberty be lost in the pursuit.”

Justice is a central principle essential for securing individual rights, maintaining social order, and legitimizing a government—an unjust government is an illegitimate government, just as an unjust law is an illegitimate law.

Justice encompasses both personal justice (a virtue individuals exercise) and political justice (the structure, purpose, and powers of government).

1. Justice as a Moral Virtue (Personal Justice)

The American Founders, drawing from classical philosophy (e.g., Aristotle) and Enlightenment thinkers (e.g., John Locke), viewed personal justice as the virtue of giving others what is rightfully due to them.

Definition: Justice involves honesty, keeping promises, respect for private property, and adherence to moral and legal obligations in individual actions and relationships.

Example: It is unjust to spread rumors that a trustworthy person is untrustworthy.

Importance: Personal justice underpins a society of mutual civic trust, mutual respect, cooperation, and friendship. A just individual honors contracts, respects property rights, and refrains from violating the natural rights of others.

2. Justice as Politics (Political Justice)

Political justice, for the Founders, was about the proper organization and function of government to secure the natural rights—life, liberty, property, and the free pursuit of happiness—of each individual citizen.

Definition: Political justice is achieved when a government derives its powers from the consent of the governed and protects the individual natural rights—life, liberty, property, and the free pursuit of happiness—of each and every citizen (and/or restores as best possible a person who has suffered unjust loss or harm).

Example: It is unjust for government to pass and enforce laws that confiscate rather than protect the property of citizens.

Importance: The Founders emphasized that justice features a government bound by the rule of law, not arbitrary power. This ensures that laws apply equally to all and are designed to protect rights rather than infringe upon them. Where there is great political injustice, moral wrongs, civil discord, and even civil war or revolution are frequent results.

Why Justice Was Central to the Founders

Moral Legitimacy: Citizens are far more likely to offer their allegiance to a just government that respects and protects their inherent natural rights.

Social Stability: Justice creates a framework for resolving disputes and ensuring that conflicts do not devolve into violence or social disorder.

Individual Flourishing: Personal justice enables people to pursue their happiness while respecting the freedoms of others and forming meaningful, important personal relationships and friendships.

Legacy of Justice in the American Founding

The American Founders institutionalized justice through the United States Constitution, creating a framework designed to prevent tyranny, uphold individual liberties, and maintain fairness in governance. They understood justice as both a personal and societal imperative—one that demanded vigilance and virtue from citizens and institutions alike.

12. Liberty

The idea of individual liberty has become so familiar to us that it’s easy to take it for granted. Yet, the idea of liberty had to be discovered and understood. A regime of liberty requires a philosophical explanation and account.

Why, after all, should people live freely? Why shouldn’t they be ruled and controlled without their consent? Why is liberty right, and the alternative wrong? Answering these questions requires an exercise in philosophic reasoning that leads to the idea of liberty.

Each human being possesses a natural right to individual liberty because each human being possesses a free mind capable of reasoning, choosing, and governing the human body inside of which the mind thinks.

Political liberty—the freedom to live as one pleases, to make one’s own choices about how to spend one’s own money and use one’s own property and labor—is the political acknowledgement of the freedom of each human mind.

There are many ways of describing the idea of a free human being governing himself as a form of personal self-government—and a nation of free men and women governing themselves, together, as a form of political self-government. In the Declaration of Independence, that idea was described as: “all men…are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights,” among which are “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”

In the most famous list of the three most important unalienable, natural rights, liberty rightfully occupies the central position.

13. Money v. Wealth

In economic terms, the wealth of one person is determined by what other people value. If you have much that other people value greatly and really want, then you’re wealthy. If other people don’t value what you have—or have to offer—then you don’t have much wealth.

Here’s the important thing about wealth: Wealth can be created. In fact, wealth must be created. That’s good news for everyone, especially those who right now don’t have much wealth: if wealth can be created, then those who don’t have much wealth can create new and additional wealth for themselves.

Wealth is created by thinking, working, and producing things that others find to be useful, helpful, or otherwise valuable. The more people value what you have produced, the more wealth you’ve created.

Poverty can be defined as the absence of wealth, as cold is the absence of heat, or darkness is the absence of light. And, just as generating heat solves the problem of being cold and creating light solves the problem of not being able to see in the darkness, so too creating wealth solves the problem of poverty.

Where people are free, productive, and create wealth, there is little poverty. Where people are unfree and unproductive, there is widespread poverty because there is very little wealth.

Wealth is not the same as money.

Money is a medium of exchange, a currency that makes it easier to trade and purchase things. Anything can be used as money. Beads, salt, silver, sea shells, and feathers have been used as currencies. In many ancient cultures there was no money at all – people simply traded the goods they made for the goods made by others in exchanges referred to as “bartering.”

When people agree to use paper money, in particular, as a currency for exchanges, that means money can simply be printed. When money is printed and the increase in the amount of money in circulation far outpaces increases in productivity, the result is inflation, which is defined as the diminished purchasing power of money. Inflation means money becomes worth less and less.

Some governments will inflate their money to levels that stretch the imagination. Between 2016 and 2019, for example, inflation rates in Venezuela were percentages that reached into the tens of millions.

A decade earlier, During Zimbabwe’s period of hyperinflation in the late 2000s, the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe issued 100-trillion-dollar bills.

These examples and others demonstrate that a person can have entire bags filled with Venezuelan or Zimbabwean money—currencies that no one values because they have been greatly inflated—and yet not have much wealth. A person can have much worthless money and still be hungry, homeless, and poor.

Money is not the same as wealth because printing money is not the same as creating wealth by producing value for others. Money is valuable only when it is in the form of a currency that other people value, a currency that can be used to purchase or trade for many things that many people value.

14. Natural Rights

Rights belong to individual human beings, not groups of people based on skin color, class, sex, or sexual preferences.

A right is a rightful claim. If you have a rightful claim to something—such as your property, or your liberty—then you have a right to the thing. The idea of individual rights is rooted in what the American Founders called “natural rights,” which are rights—and rightful claims—that exist by nature.

Simply by virtue of sharing human nature, every human being possesses a right (and has a rightful claim) to one’s own life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, as the Declaration of Independence reminds us.

Every human being possesses these rights by nature, which is to say they are natural rights.

Individual natural rights are also unalienable. In the context of the Declaration of Independence, unalienable refers to rights that are inherent and cannot be taken away—or transferred from one person to another—because they are derived from the very nature of being human.

Someone might steal your wallet or purse, for example, yet you still have a rightful claim to your wallet/purse after it has been taken. That is why theft is wrong, and why it is right to return something that has been stolen.

Stealing property from an individual is wrong. Stealing a person’s natural right to his own property is impossible. Stealing someone else’s life—i.e. murder—is wrong. Stealing someone’s natural right to life is impossible.

The natural rights of an individual can be violated, but no one can take away natural rights. Your natural rights, as a human being, cannot be alienated from you. They are unalienable.

15. Power

Power, within the context of politics and government, is the capacity to influence, control, and direct the behavior of individuals, institutions, and even entire societies. At the end of the first chapter of his famous Second Treatise Of Government, John Locke defined political power this way:

Political power, then, I take to be a right of making laws with penalties of death and consequently all lesser penalties for the regulating and preserving of property, and of employing the force of the community, in the execution of such laws, and in the defense of the commonwealth from foreign injury; and all this only for the public good.

Another way to describe political power is to say that government is the monopoly on legalized force. Only government passes laws and enforces laws with armed police who are backed up by courts, judges, and prisons. No business and no other organization of any kind other than government has the legalized power to detain or arrest you, legally confiscate your property, and legally deprive you of your liberty, even your life (in cases of capital punishment).

Government is force. Government is legalized force.

Power in the form of legalized violent force is the lifeblood of any government. Remove power and legalized force from a government and it is no longer a government.

Yet, the dual nature of political power—as both a tool that can be used to protect the individual rights of citizens, and a potential instrument of tyrannical and unjust oppression—has inspired centuries of philosophical reflection. Three perspectives—Lord Acton’s warning about corruption, Aristotle’s insight into character revelation, and the American Founders’ institutional skepticism—illuminate the complexities of power and its governance.

Lord Acton: “Power Corrupts, Absolute Power Corrupts Absolutely”

The 19th-century historian Lord Acton famously argued that power inherently tempts individuals to abuse it, particularly when unchecked. His maxim underscores the psychological and moral risks of concentrated authority. When leaders face no constraints—whether legal, institutional, or cultural—they often prioritize self-interest over public good.

History offers stark examples: tyrants like Joseph Stalin and Chairman Mao wielded absolute power, resulting in widespread oppression and atrocities. Acton’s warning reflects a pessimistic view of human nature, suggesting that even well-intentioned individuals may succumb to corruption when insulated from accountability. This insight is the reason wise people demand a government in which power is separated, dispersed, and constitutionally limited.

Aristotle: Power Reveals Character

In contrast to Acton’s focus on corruption, Aristotle posited that power does not inherently corrupt but instead reveals virtues and vices within an individual. In the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle argues that an individual’s true character is best revealed for others to see when that individual gains authority and power.

A virtuous person, entrusted with power, will act justly, while a person easily tempted by vices may descend into tyranny. Consider Marcus Aurelius, the Roman emperor whose Stoic philosophy guided his equitable rule, versus Caligula, whose reign devolved into cruelty, excess, and great acts of injustice.

Aristotle’s view implies that governance depends on cultivating moral leaders, as power amplifies—rather than creates—their ethical inclinations. This perspective complements Acton’s by acknowledging that institutional checks alone are insufficient; true statesmanship requires the moral and intellectual virtues.

The American Founders: Power Is Both Necessary and Dangerous

The Framers of the U.S. Constitution synthesized these ideas, recognizing that government must wield enough power to prevent chaos and protect individual rights, but not so much that it threatens liberty.

James Madison wrote in The Federalist No. 51: “If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary.” This tension—between power and freedom—shaped their design.

The Founders institutionalized skepticism of power through mechanisms like federalism, separation of powers, and constitutional checks and balances. By dividing authority among branches and levels of government, they ensured ambition would counter ambition, preventing any single entity from monopolizing control. For example, Congress checks presidential overreach via impeachment, while states retain autonomy under the Tenth Amendment. These structures reflect Acton’s fear of corruption but also align with Aristotle’s emphasis on accountability, as leaders are forced to justify their actions within a competitive system.

The American Founders took extra steps, too, to prevent the centralization of unchecked power in government by openly promoting freedom of the press, religious liberty, and educational choice. Should those in government try to centralize too much power for themselves, they will likely be challenged by intelligent and informed civic opponents.

The dual nature of political power—as both necessary and highly dangerous—demands a governing framework that harnesses its potential while curbing its risks. Acton’s corruption thesis, Aristotle’s character revelation, and the Founders’ institutional ingenuity collectively argue that effective governance requires both moral virtue on the part of people and the politicians they elect, combined with wisely designed institutions and structures of government power.

16. Profit

Businesses can have multiple purposes, but the primary purpose of every business is to be profitable. When a business doesn’t make a profit, the business usually closes. It makes no sense, after all, and usually becomes impossible to keep a business open when it’s losing money and not profitable.

The question we want to address here is: What exactly is profit? To which we offer an unusual answer: Profit is the happiness of others symbolized by money.

A business makes profit by making other people happy.

That’s probably worth repeating: A business makes a profit by making other people happy. When a business makes lots of people happy by providing products and services that people value, appreciate, and find helpful, that business is likely to be profitable.

To be profitable simply means that (some) people value the products or services a business offers to sell more than the cash in their pockets—some people are happy to trade their cash for those products. Why might that be? Let’s explore this subject by addressing some additional questions.

Why would anyone trade cash for some product or service offered by a business? And how exactly does a business make a profit from that trade?

A customer trades his cash for a business product because he values the product more than the cash, in large part because it would cost him far more cash than the price tag the business put on the product if he tried to make the product himself.

A business can usually make a product far more efficiently and at much lower cost because that’s what business is: specialized labor and resources organized to make certain products or offer certain services very efficiently. A business can charge a price that’s higher than what it cost the business to make the product, but much lower than what it would cost a typical person if he tried to make the same product on his own, from scratch.

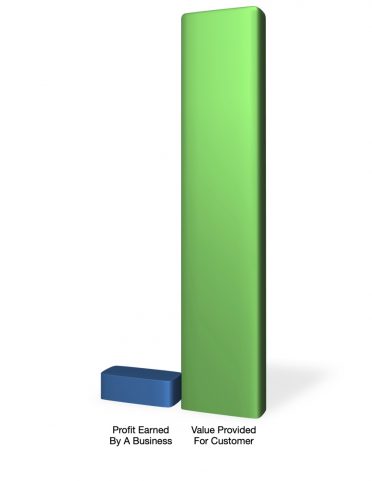

When the sale price a business charges a customer for a product is higher than the cost to make the product, the difference is profit.

When the price a customer pays for a business product is lower than the price it’d cost him to make the product on his own, the difference is the value he receives from the efficiency of the business – and that value is why a customer is willing to pay the sales price for a product, which translates into profit for the business.

The “profit margin” for most businesses – meaning the difference between the sales price of a product versus the cost of making it – is typically quite small. Often, it costs a business almost as much to make, market, and distribute a product as the price for which the product is sold.

However, the value margin for most customers – meaning the difference between how much it costs to buy a product from a business versus how much it costs to try and make the product by oneself from scratch – is usually enormous. Usually it would cost a person hundreds, thousands, or even millions times more to make a product from scratch than to buy it from a business.

Imagine trying to make from scratch the ordinary devices you use every day, such as your smart phone, computer, or car. Imagine the costs in both money and time if you were to hire researchers and engineers, and try to collect all the raw and processed materials from around the world that you’d need to make any of those products.

That’s why almost always, the value for customers is much greater than any profits earned by business. Stated differently: No matter how much profit a business earns, it pales in comparison to the value that business provided for its customers. And receiving so much value from the specialized, organized productive work of people within a business is a source of great happiness. That is why the more profit a business earns, the more happiness a business produces for others.

17. Proper Purpose of Government

Many political disputes arise over disagreements about what government should or should not do. It is one thing to say that people who are sick often value health care; it is something quite different to insist that government should provide health care for everyone. It is one thing to say that education is important; it is something quite different to insist that government should provide education for everyone.

Civic harmony requires fellow citizens who share some common understanding about the proper purpose of government, which is succinctly summarized in the Declaration of Independence.

After positing “that that all men are created equal” in the sense that all human beings are “endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights,” among which are “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness,” the Declaration rightfully states “that to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.”

The proper purpose of a government, therefore, is a fairly limited goal: to “secure” the equal individual natural rights of each and every citizen who is within the jurisdiction of that government.

To be clear, the proper purpose of a government is not to protect the natural rights of every human being on Earth. Citizens in other parts of the world should form their own governments that protect their own rights.

Also, the proper purpose of government is not to save the souls of citizens or force them to profess “correct” religious beliefs. The proper purpose of government is not to provide or give to citizens whatever they want. Anything that requires the labor and capital of others—anything that requires the property of others—cannot be a right, should not be an entitlement, and it ought not be supplied by government.

The proper purpose of government is limited to protecting the natural rights of citizens, which is why a proper, legitimate government should have only limited powers—those powers necessary

18. Property

In a 1792 essay titled “On Property,” James Madison offered an excellent and comprehensive definition of property, from which we quote at length:

In its larger and juster meaning, [property] embraces everything to which a man may attach a value and have a right; and which leaves to everyone else the like advantage.

In the former sense, a man’s land, or merchandize, or money is called his property.

In the latter sense, a man has a property in his opinions and the free communication of them.

He has a property of peculiar value in his religious opinions, and in the profession and practice dictated by them.

He has a property very dear to him in the safety and liberty of his person.

He has an equal property in the free use of his faculties and free choice of the objects on which to employ them.

In a word, as a man is said to have a right to his property, he may be equally said to have a property in his rights.

A person’s property, in other words, certainly includes external physical objects, such as someone’s house, car, and cash money. Property also extends to a person’s body and the safety of it, as well as one’s labor and his religious opinions and his freedom of speech.

Your property is everything that is rightfully yours. In this enlarged understanding of property, the term is synonymous with liberty. Where people are fully protected in their property rights, their liberty is secure.

As Madison concludes, the right to property is important and the very concept of rights implies and requires the idea of property: Your individual natural rights are your property. They belong to you.

19. Regulations

The premise of typical statutory laws in the United States, such as criminal and tort laws, is individual freedom rooted in mutual civic trust: A citizen is free to do whatever he pleases unless and until he violates the rights of others, causes some kind of noncriminal damage to someone else, or does something (such as violates a contractual agreement) for which he can be civilly sued.

After a citizen has criminally or civilly injured someone else, criminal laws offer punishments and civil laws offer remedies.

Regulations, however, are strikingly different from traditional statutory laws. The premise of regulations is not individual freedom because there is no mutual civic trust. The premise of regulations is suspicion, distrust, and government supervision over individuals.

The foundational assumption for all regulations is that each citizen will do something deceitful, purposefully harmful, or irresponsibly damaging, sooner or later, so rather than wait for a wrongful action, regulations control citizens before they have an opportunity to harm to anyone.

In many different industries, there are staggering, often insuperable costs and burdens of complying with regulations before the doors of a new business are even opened. A business owner literally has had no opportunity to hurt anyone with her business because he has yet to open her business, but that does not stop government bureaucrats from regulating what he does.

Laws v. Regulations: Elected Legislators v. Unelected Bureaucrats

Everyone who remembers the old Schoolhouse Rock video knows how a bill becomes a law: A majority of the elected members of the House of Representatives and a majority of elected Senators vote in favor of a bill, which is then typically signed by the elected President of the United States, and the bill becomes a law.

The process of making laws is similar within state governments: Elected legislators vote for a bill, which is then usually signed by an elected governor.

At both federal and state levels, those empowered to create laws are elected by those to whom the laws apply. This is an important check on government power. If elected legislators and government executives (like the President or state governors) create laws that are unwise, unjust, or unconstitutional, citizens have an effective recourse at the next election: They can vote others into office, thereby removing from office those elected officials who were responsible for the bad laws.

Moreover, laws are passed, enforced, and judged by three separate branches of government. This, too, is a check on government power. If a legislature, for example, passes a law that provides some illegitimate advantage for legislators, it will be enforced by the executive branch and judged by the judiciary, both of which are independent from the legislative branch of government.

Regulations, however, are not passed by any elected representatives or officials. Regulations are rules issued by unelected bureaucrats who cannot be removed from positions of government power in the next election.

This is deeply problematic because while regulations are not, technically, laws—they’re neither voted on by elected legislators nor signed by an elected executive—regulations have the power of law when enforced by government agents and adjudged in courts (or quasi-judicial administrative hearings).

Regulations are binding on citizens—regulations prohibit citizens from doing certain things, and command citizens to do other things—as if they were laws. Yet, regulations are not laws.

To boot, regulations are typically issued, enforced, and judged by the same regulatory agency. There is no separation in the realm of regulatory power.

For ordinary citizens, in the course of ordinary civic life, violating a regulation is no different than violating a law. A citizen can be fined, punished, even imprisoned, simply for not being in compliance with a regulation.

Laws v. Regulations: Presumed Innocent or Guilty?

The premise of typical, statutory laws—both civil and criminal—is that a citizen is presumed to be innocent until someone else proves that he is guilty of some illegal act or causing some kind of harm or injury.

Whether it is a case involving civil or criminal laws, the laws command action only after it has been proven that someone has acted criminally or has acted in ways that make them accountable to civil laws.

The premise of regulations, however, is that a citizen is presumed to be guilty unless and until he proves that he is not guilty. The process of proving one’s own guiltlessness is called: compliance.

Failure to be in compliance, just once, will likely result in the government punishing you, perhaps harshly, as if you had been convicted for some criminal offense or found by a civil court to have caused great harm to someone. You might be fined by the government, or your business might be shut down, or worse—not because you violated anyone’s rights, but simply because you did not prove to the satisfaction of government bureaucrats that you are obedient and compliant.

The entire premise of regulations is that you, the citizen, are presumed to be guilty until you prove that you are not guilty.

Laws v. Regulations: Burden of Proof

In the case of civil and tort laws, the burden of proof is on the person accusing someone else of causing damage or violating a contractual agreement. The accuser must prove in civil court that the other person actually did what he is accused of doing.

If you, for example, sue someone for failing to do some work they contractually agreed to do, the burden will be on you to demonstrate what the contractual agreement was and that the work was not done in the way it was agreed to be done.

In the case of criminal laws, the burden of proof is on the government. The government must prove—beyond a reasonable doubt—usually in front of a jury—that the citizen accused of violating criminal laws did indeed violate criminal laws.

Whether a person accused of crimes actually committed those crimes or not, he walks free if the government cannot prove that he committed those crimes. That is why the verdicts are either “guilty” or “not guilty” in criminal cases. There is no verdict of “innocent.” The government either proves that a person is guilty of a crime, or the government fails to prove that a person is guilty of a crime.

With regulations, however, the burden of proof is upon you, the individual citizen. You must prove your own guiltlessness by demonstrating that you are compliant. Further, you do not demonstrate that you are compliant once, or twice, or three times. The process of proving one’s own guiltlessness to unelected bureaucrats and regulators—the process of compliance—is an endless process.

As every business owner knows, being in compliance last reporting period means nothing for the next reporting period. You must prove your guiltlessness by being in compliance over and over, without end.

In the modern United States, at the federal level alone, government agencies create tens of thousands pages of new regulations each year. This fact presents an important question to be discussed with students: Is a bureaucratic regime of regulations compatible with the idea of the rule of law?

20. Revolution

When a government violates rather than protects the equal, individual natural rights of citizens, the people may peacefully alter their government by adopting new laws or even a new constitution.

When no peaceful remedies for government injustice are possible, the people have a natural right to abolish their government—by violent revolution, if necessary—and replace it with a new and more wisely-designed government.

Government has only the few powers that We The People grant to it through our Constitution. To keep government from exercising or abusing powers the people never granted, citizens can remind elected representatives now and then that the people retain the natural right to alter their government or to abolish it through revolution.

At the same time, citizens should always understand that revolution is dangerous. When an entire nation dissolves their own government and ignores the laws that government created, there is no guarantee that the rule of law, ordered liberty, and justice will follow.

Sometimes, as in the example of the French Revolution, revolution can become almost impossible to stop. Even after a bad government has been removed by revolution, revolutionaries will often direct their violence at anyone who attempts to establish some form of governance, social order, or law, and the transformation of revolution into tyranny is not only possible, it is likely.

21. Risk

Nobody creates more value or improves the quality of human life more than entrepreneurs. And what distinguishes entrepreneurs from non-entrepreneurial people? Their willingness to accept high levels of risk—calculated, strategic, and informed risk, but still, risk—including risking their own capital up to and soften including everything they own.

Entrepreneurs accept extraordinary risks that far surpass those faced by ordinary employees. Their willingness to risk losing financial resources, stability, and even their own health and personal well-being drives entrepreneurial innovation, economic growth, and social progress. Here’s why the risks of entrepreneurs matter and why others should be grateful:

1. Risks Unique to Entrepreneurs

Entrepreneurs face existential risks that employees rarely encounter:

Employees don’t have these worries. The most an employee risks, typically, is working two weeks without receiving a paycheck, at which point a typical employee would quit and look for another job.

2. Why Employee Risks Are Smaller

Employees operate with built-in safety nets:

3. The Entrepreneur’s Gamble: High Risk, High Reward

Entrepreneurs risk everything not just for profit, but to solve problems and create value. Their bets yield societal benefits even when they fail:

4. Why Society Should Be Grateful

Entrepreneurs accept risks that others avoid, enabling real social, cultural, economic, and material progress:

The Paradox of Risk

While employees contribute stability, entrepreneurs drive transformation. Their willingness to “risk everything” is not reckless—it’s a calculated risk, usually after great study and analysis of a market, for potential reward. Society benefits disproportionately: A single successful entrepreneur can uplift thousands (e.g., Henry Ford’s assembly line revolutionized labor and mobility). Even failures (e.g., bankrupt startups) refine markets and spur new ideas.

Conclusion

Entrepreneurs are society’s risk-bearers, gambling personal security to advance collective prosperity. Their courage to fail—and resilience to try again—creates the innovations, jobs, and opportunities that define progress. While employees provide essential stability, entrepreneurs propel us forward. Gratitude is owed not just for their successes, but for their willingness to shoulder risks that few would dare. Risk-taking entrepreneurs are heroes we should celebrate.

22. Rule of Law

The rule of law stands as one of the most important discoveries in the history of political science. The opposite of the rule of law is the arbitrary rule of individuals and the unpredictable exercise of government power.